A Conversation

on Collaboration

An Öresund extravaganza brought together three artists from across disciplines for a sweaty mash of grit and riffs music, dance, and visuals — the result of a SHAPE+ supported residency at Inkonst. Over five days, Statoil, Sanna Blennow, and Tobias Toyberg-Frandzen built something from scratch: part performance, part experiment, and fully alive in its instability.

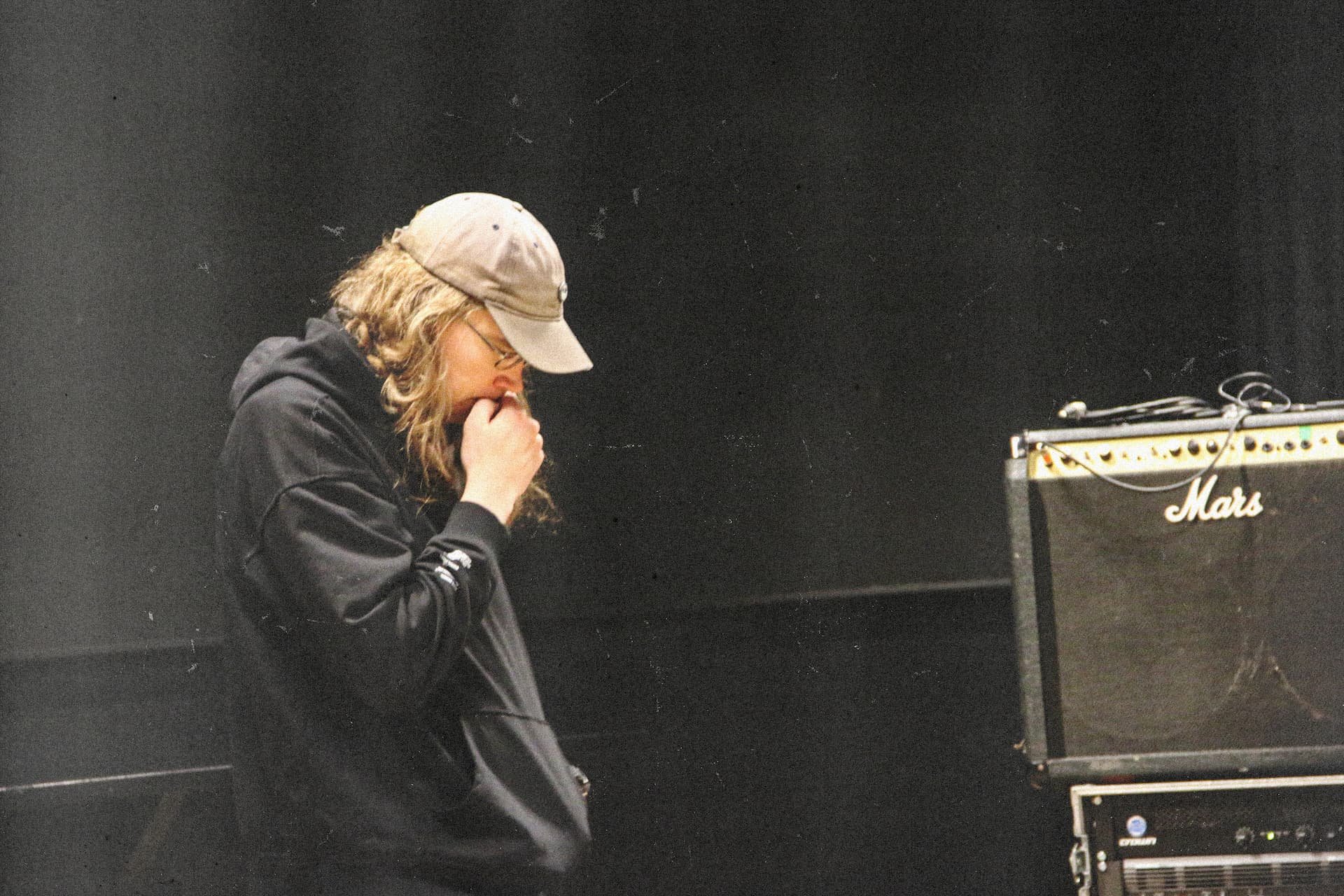

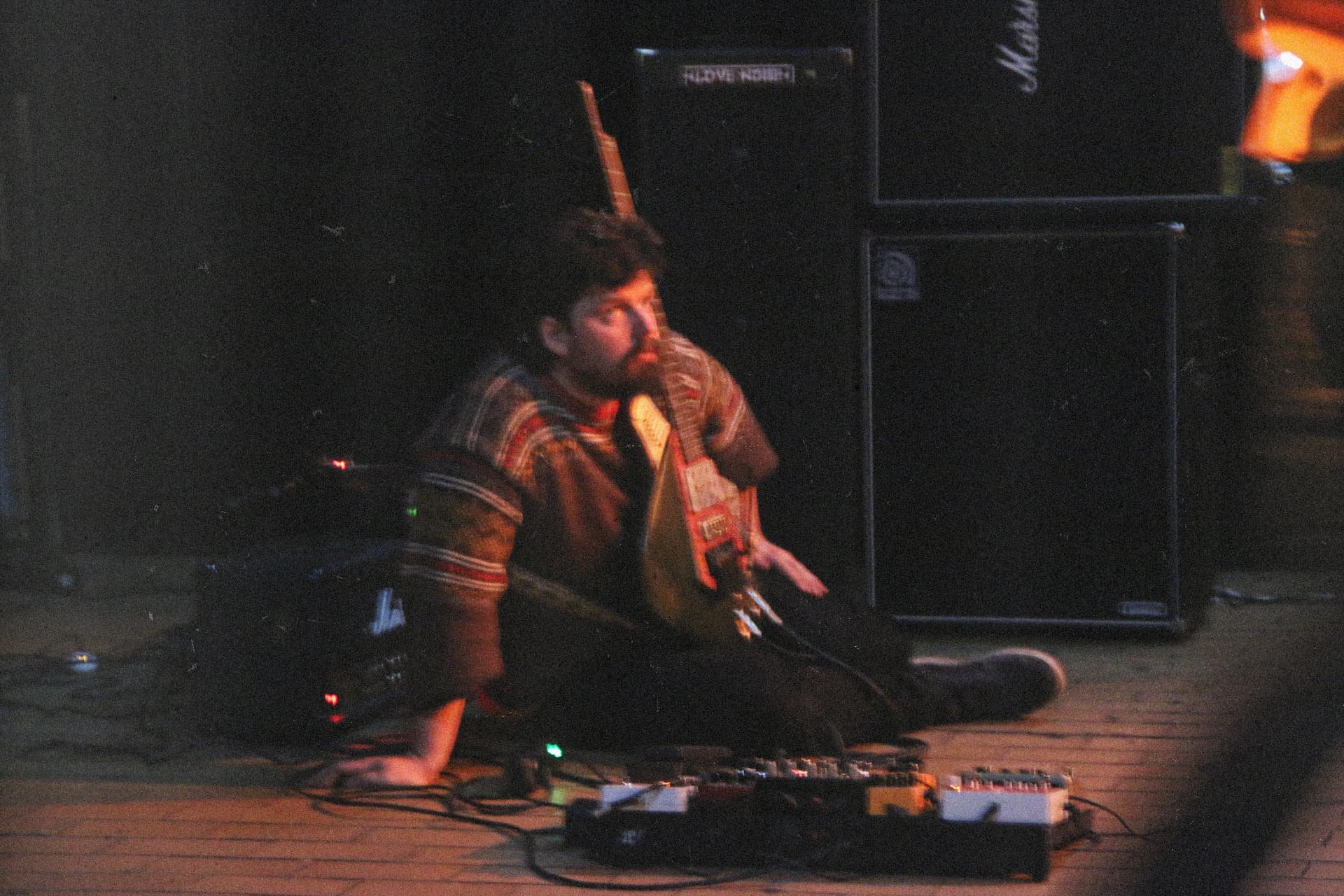

Copenhagen-based Statoil — the only known representatives of the genre “static-oil-core” — channel a chaotic resistance through heavy, repetitive riffs and shrieking noise. Their music feels like a middle finger to hyper-capitalism, raw material extraction, and compassionless systems. Statoil is John Arne Rånes on Gitar Ordinarium, Jonatan Uranes on bass, and Sjur Vidar Lilleås on drums.

Swedish choreographer, performer, and educator Sanna Blennow works in the grey zone between the black box and the white cube — a space between set choreography and improvisation, sanctuary and rupture. Her practice navigates time, memory, and the in-between, where the body becomes a vessel for intuition and the monsters are allowed to come out.

Photographer and multidisciplinary artist Tobias Toyberg-Frandzen has been crafting digital visuals since 2001, blending garish wit with visceral impact. Known for his collaborations with Vanligt Folk, Statoil, and Pig Wrestler, his work lends a delirious energy to live performances and projected worlds.

We spoke to the trio the day before their open studio showing, as they navigated the final hours of a collaboration that was as much about process as performance.

What happens when three distinct practices collide under time pressure, with no fixed outcome?

The Initial

Uncertainty

“..a forced marriage..”

Sjur: Where do you see yourself five years from now?

Haha…Actually, my first question is — what did the starting point of this collaboration feel like? Was it structured from the beginning, chaotic, or something in between?

Sanna: The framework was clear enough: five days to create something that we’d present. But I wasn’t sure who was taking the lead or how we’d manage the project. It felt like a blind date — or even a forced marriage — because none of us really knew each other. I came in curious and open to experimenting, but there was still a sense of, “Wait, how do we actually do this?”

Jonatan: A complicating factor was that this was a collaboration within a collaboration. We’re already a group with its own dynamics, its own artistic language, and we’re still evolving. So, we had internal discussions about how to define things — what the boundaries are, what’s flexible, what’s not. Then add dance, which we had no prior experience with, and suddenly, it’s hard to imagine how everything will come together.

Tobias: To me collaborating is a natural state of productivity since I always create images for sound and performance. It’s easy when you work with other creative minds, free spirits, and unlimited freedom of expression.

Finding Common

Ground

“It felt like a dome that

was hard to penetrate.”

Sanna: Their music is dense and multilayered, so it’s hard to find breathing spaces where movement can have agency. Early on, we experimented with spreading out in the room, looking for intersections between movement and sound, but it wasn’t easy. It felt like a dome that was hard to penetrate.

John: Yeah, the first evening we played together, we were experimenting with lighting, and at first, Sanna was dancing under bright lights while we were focused on our instruments — it was hard to see how it fit. But then we turned off the lights and used only a flashlight, and suddenly, the whole thing made sense. She was doing the same movements, but the shift in lighting created a space where her presence made sense. That was a big realization.

Sanna: Then we had another breakthrough. They introduced a contact mic, and I experimented with my body making sound. It created this dynamic where movement and sound started to influence each other more directly. That moment felt like a step toward finding common ground.

The Role of Tension

“But it’s not a happy party.”

Statoil’s music carries this sense of urgency — it feels like something is pushing forward, like a decision has to be made in the moment. Do you have a specific feeling you want the audience to walk away with?

Sjur: For me, it’s important that the music is both chaotic and inviting. It has to have a groove — something that makes people want to move.

Jonatan: Not necessarily. More like… it should be something people remember, something that spreads, something that lives in their brains. Almost like a virus.

When you perform, does the music make you move physically?

John: It’s hard not to… it’s very physical with all the speakers. That’s probably why I want other people to move too.

Would you say it’s more about tension or more trance-like?

John: It’s somewhere in between. More like a machine — repetitive, relentless. Not necessarily meditative, but it could be if you focus on it in a certain way.

Like a machine in what sense?

John: Like an evil machine — mechanical, unstoppable. It could be the physical machine, or the machine of capitalism, or ideology, or all these systems we live in.

Jonatan: But would you dance to an evil machine?

Sjur: Well, everyone loves Darth Vader. He’s evil, but he’s still cool.

But it’s not a happy party.

Sjur: No, but even if you see all this evil in the world, you’re still part of it. You consume, you produce waste — you acknowledge it, but you keep living. Maybe that’s part of what this music expresses.

Tobias: I try to make beauty out of doom, and vice versa.

The Unfinished

Work

When you’re creating a piece, how do you know when it’s finished?

Sanna: I mean, I recently did a solo performance, and at many points along the way, it felt finished — partly finished, then more finished — but it wasn’t truly complete until the premiere. Even then, during the four performances at that venue, it still felt unfinished because it’s a live act. The structure was finalized, but what happens within that structure always changes because it involves human interaction.

Then it went on tour, and I realized it’s actually good when it’s not completely finished. It leaves room for growth or reshaping. That’s often the case when I make performances for the theater. We move in, set everything up, and work on it until the day before the premiere. On that day, we’re like, “Okay, this is it.” But even after the premiere, some small adjustments can happen, though the core remains the same. It’s similar to what you said earlier about the interplay between choreography and improvisation.

Tobias: It’s a one-off situation. I’ll wait to be pleasantly surprised watching the final presentation/performance.

If you could describe this collaboration in a single sentence, what would it be?

Tobias: Trust the process.

Ultimately, collaboration isn’t about certainty — it’s about making space for the unknown. And sometimes, the most meaningful moments arrive not when things feel finished, but when they remain in motion.

Text and photos:

Nadiya Vasylyeva @vasylyevan

Artist(s) of the SHAPE+ network. SHAPE+ is a European platform for innovative music and interdisciplinary art co-funded by the European Union and Pro Helvetia

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.